tl;dr — Spectaculars is a comic book superhero TTRPG. I love Spectaculars. It’s your own comic book universe in a box.

This post is not a critical review of Spectaculars. It’s more of a deep dive and celebration of one of the best TTRPGs I have ever played. This is also a long one, as I have lots to say about this game.

Table of Contents

- A Game About Heroes

- A Game About Villains

- A Game About Setting

- AC 100 System

- Narrative: Interlude Scenes

- Conflicts: Drama and Combat

- A Hero’s Journey: Advancement

- Conclusion

Beneath the towering, neon-lit skyscrapers of Edge city, deep in the bowels of its poverty stricken Grifter’s Alley, the vigilante known as The Roadkill patrols the damp streets in his modified tank. A serial killer is on the loose, and Roadkill won’t rest until the streets are safe.

Hidden beneath an abandoned, haunted church, the ghost of an ancient wizard makes a pact with the occult government agent, LeShade. The Nether Realm threatens to consume the waking world if they can’t work together and restore the ancient seals of binding in time.

On the other side of the galaxy, the galactic protector Time Knight and her super-powered hillbilly partner Clusterflux enjoy a cold one aboard an interstellar truck stop orbiting a black hole. The dragonoid space bounty hunter, Beith’ir shows up to bring Clusterflux in for his galactic gambling debts, when the station is suddenly attacked by a hostile alien bug swarm.

Within their headquarters in downtown Edge City, the cybernetic super soldier The Rook, the hyper intelligent monster Benny, and their leader Professor Power fight an impossible fight against their evil selves from a darker timeline, in a battle for the multiverse.

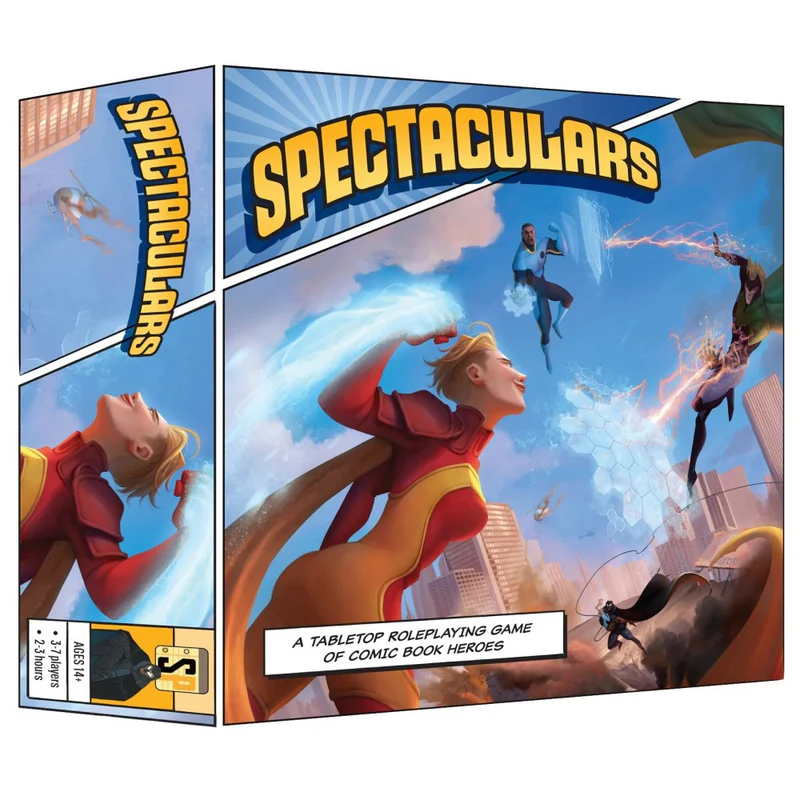

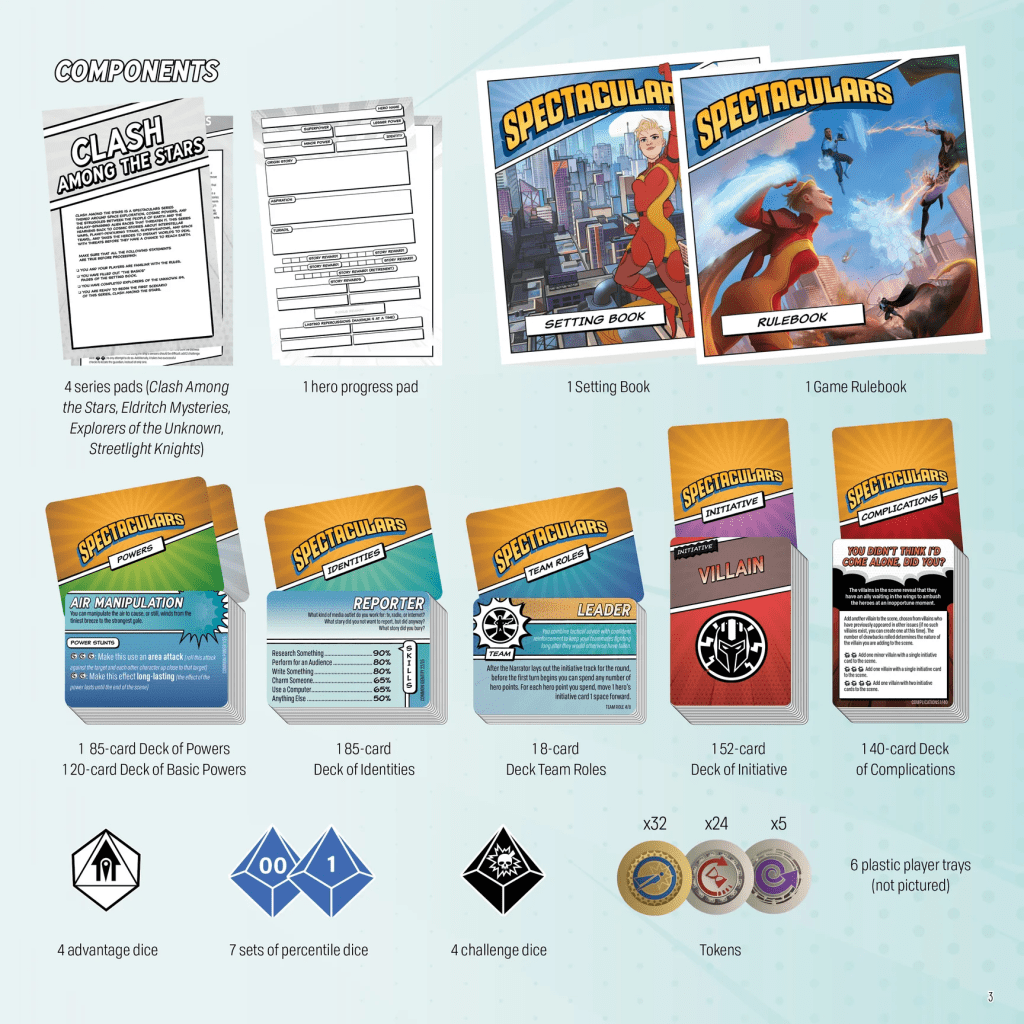

Fifty-some sessions, about a year’s worth of playing once a week, Scratchpad Publishing‘s Spectaculars gave me and my group some of the best time playing a TTRPG. Countless superheroes and their teams, just as many villains and evil plots and staples in the genre, and all that from so simple a box:

- Core rules for playing and running the game

- A setting book that is core to creating your own, unique comic book universe

- Character cards for powers, identities, and team roles

- Four series pads, which functions as themed campaigns, each with 12-13 issues (adventures)

- Streetlight Knights (Street Level)

- Explorers of the Unknown (Super Science)

- Eldritch Mysteries (Supernatural)

- Clash Among the Stars (Space/Galactic)

- Character sheets for all the different hero archetypes

- Tokens that are used during play

- Dice for the 100AC system, which includes percentile dice (d100), four advantage dice, four challenge dice

It’s a complete game in a box that gives you everything you need to create your own comic book super hero universe.

A Game About Heroes

Agent LeShade drew another circle of black ink across his forearm; the pain seared his flesh and spirit alike. Ever-present in the corner of his eye, the shadow demon seemed to smile.

“You like that, Malinka, don’t you? Every tattoo another nail in my coffin, I get that.” The soul-bound demon said nothing. “But without these powers, I can’t stop the Reverie from devouring the waking world. Can’t think of a worse hell, if you ask me.” Another draw of the needle infused with darkness.

“I can, Sorcerer,” said Malinka. “The Reverie is a soft dream on a warm autumn’s eve compared to the nightmare from whence your magic flows.”

LeShade almost laughed as he closed the last arcane sigil of his new tattoo. “One hell at a time, then. I’ll be rid of you and your master soon enough.”

Spectaculars is a comic book superhero game. As such, it aims to create a fully realized comic book universe of superheroes and their villains. It focuses on the drama of comic books, instead of comparing power values and ratings between different heroes. It’s not about the numbers or statistics or levels. It’s about their identity, their ambitions, hopes, dreams, and also about the shortcomings, their fears, the times they fail despite (or because of) all that strength.

It’s about Spider-Man trying to finish high school or asking MJ out or keeping his aunt safe, not about how his super strength compares to that of Captain America. It’s about Batman donning the mask of the playboy billionaire during the day and the toll his two different lives take on his soul, not about the stats of his bat mobile or newest bat-gadget.

Comes right down to it, superhero stories aren’t any different than any other soap opera or action flick, just with silly costumes, outlandish villains and their plots, and ever-increasing stakes and complications. And Spectaculars captures that so damn well.

It starts with character creation. You might be forgiven for thinking that you come into this game with an idea or inspiration in mind already. Something like a web-crawler, or a caped crusader. But Spectaculars makes you rethink any preconception you might have. Character creation is partially random. It’s best to come into this game with no big idea in mind.

Characters are made to jump straight into the action. You can worry about all the other stuff later.

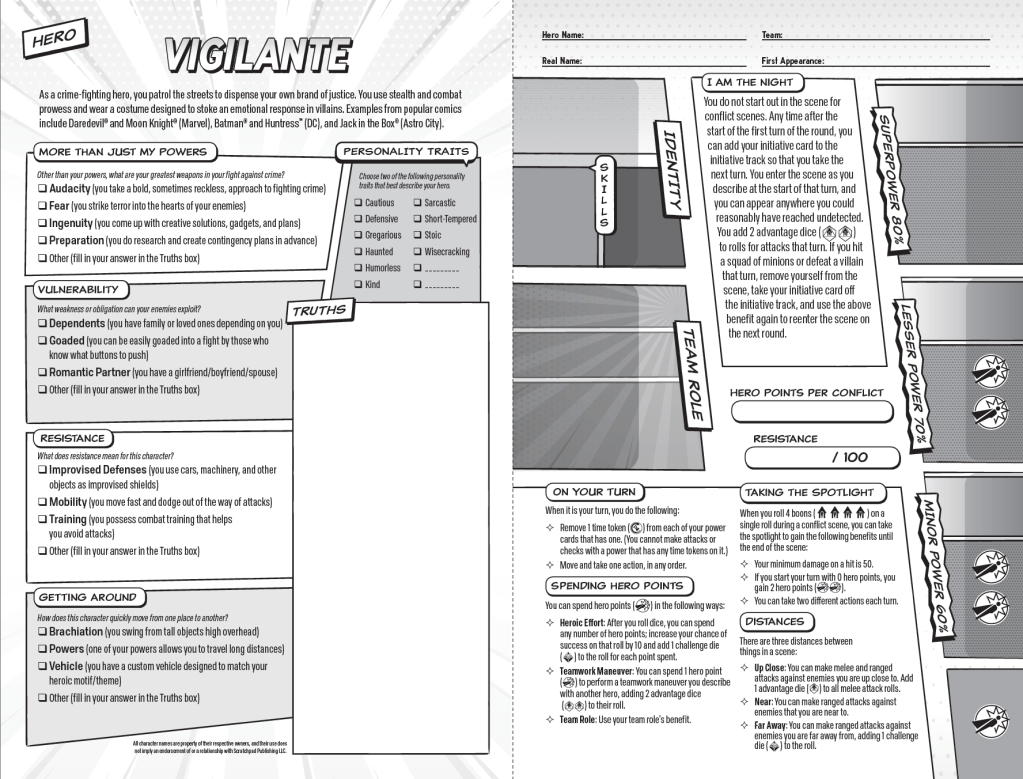

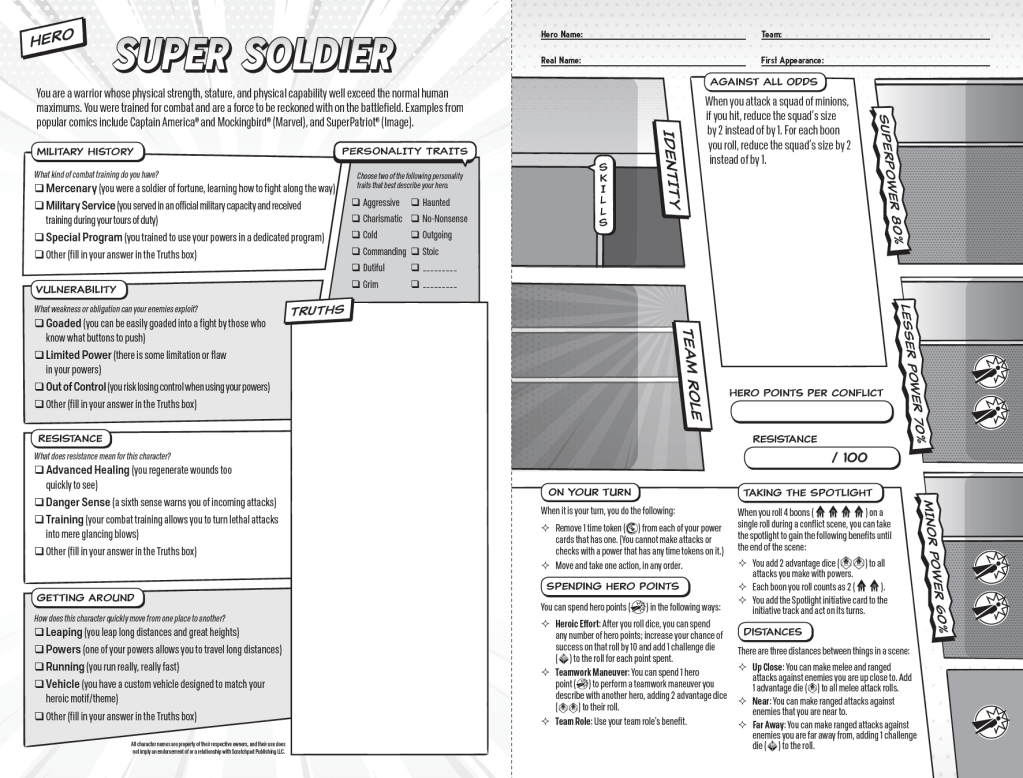

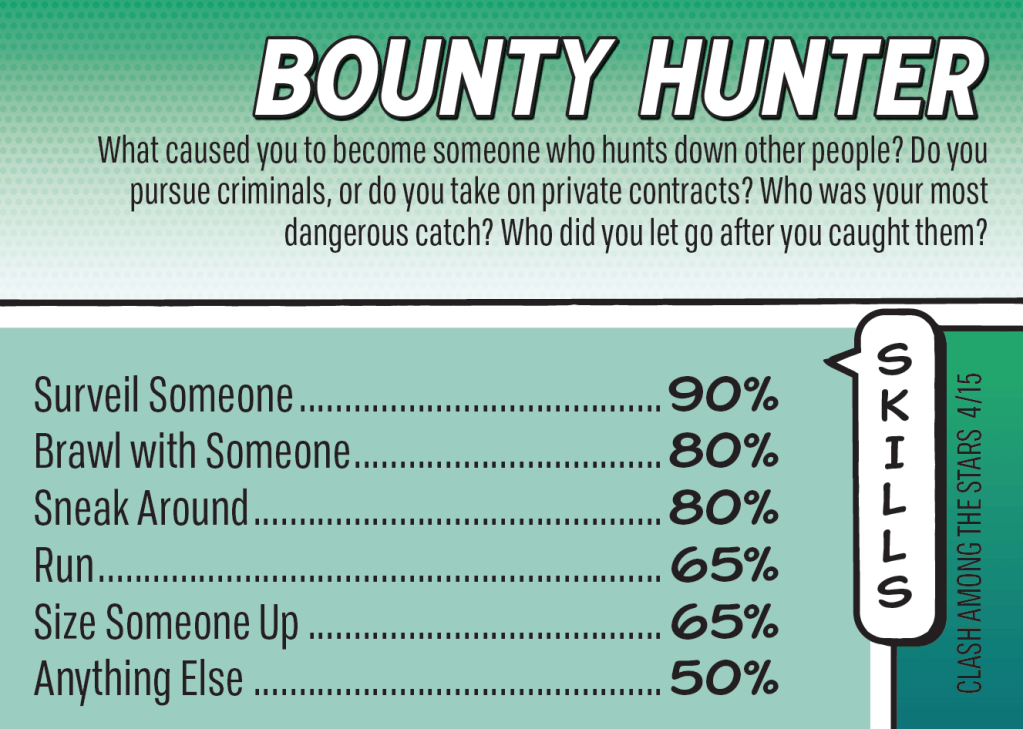

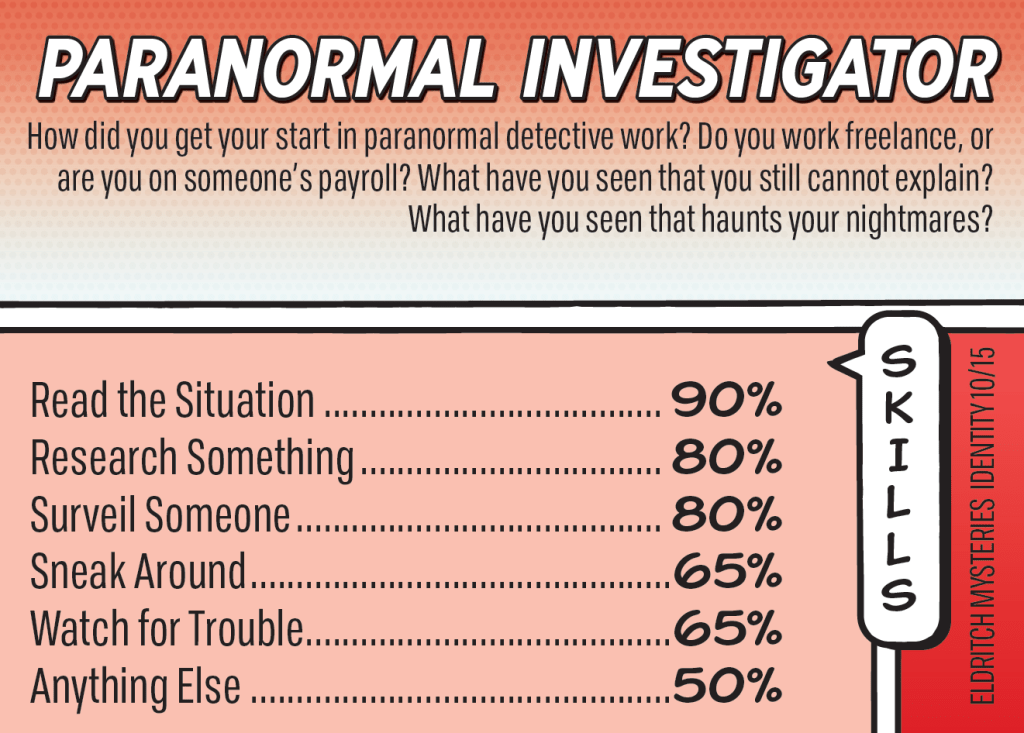

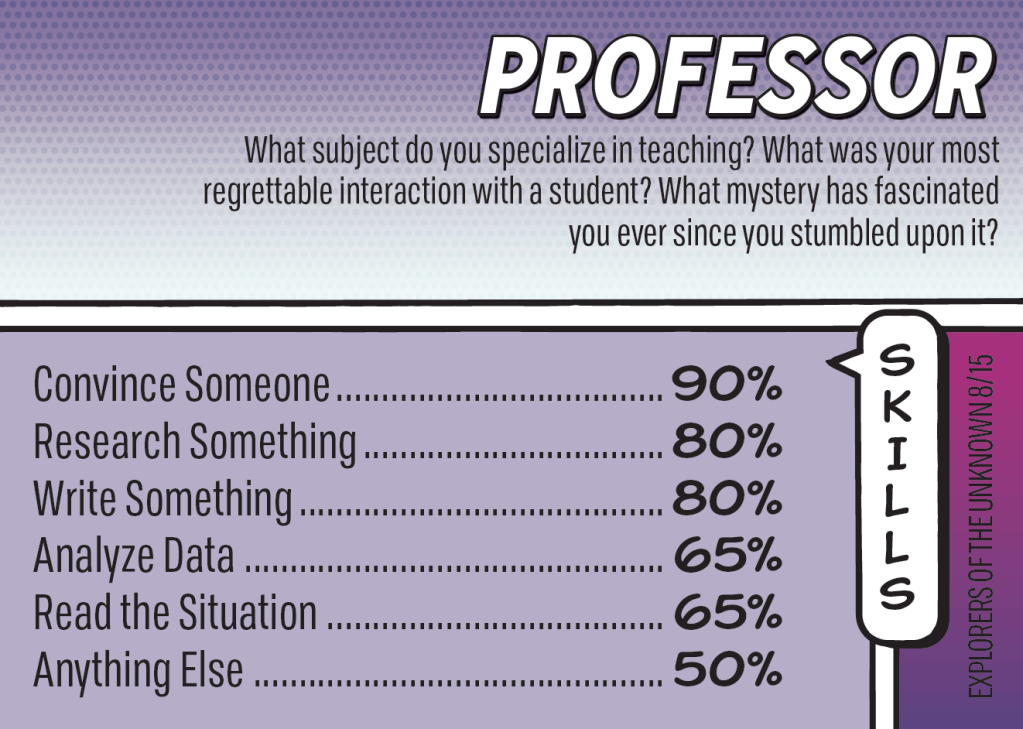

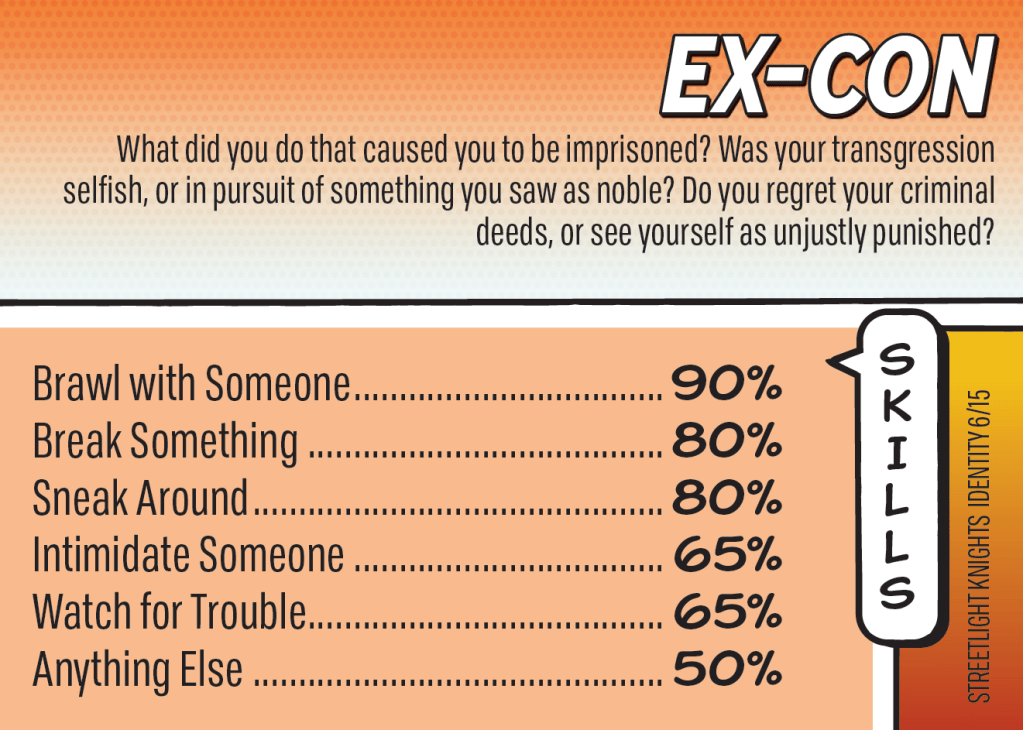

First, you choose an Archetype. Here, you get to make an informed decision about the foundation of your character. Are you a Street Sentinel, a Sorcerer, a Power-Armor Pilot, or Powerhouse? Each series has their own six recommended archetypes, and playing through a series unlocks a few more. Players get to choose an archetype from the series they are playing, or, if the GM is up for it, from another series. Sometimes Constantine teams up with Batman, right?

Each archetype has a basic power, a way to handle Spotlight (more on that later), and a short questionnaire tailored to the archetype but following the same basic setup:

- How is your archetype expressed?

- How do you withstand being injured?

- What’s your weakness?

- How do you enter a scene/get around?

Crucially, you might notice, the questions aren’t “What’s your origin story?” or “Where do you come from?” That’s because you’re not meant to think about these things yet. At least, don’t commit to any ideas you might be getting at this point.

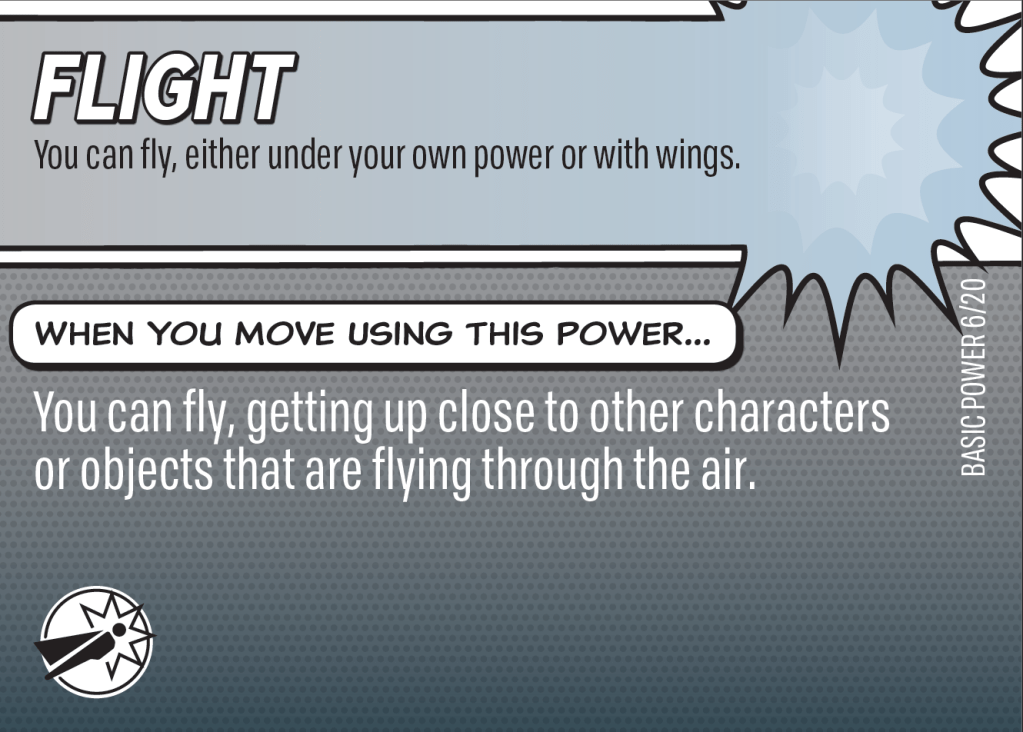

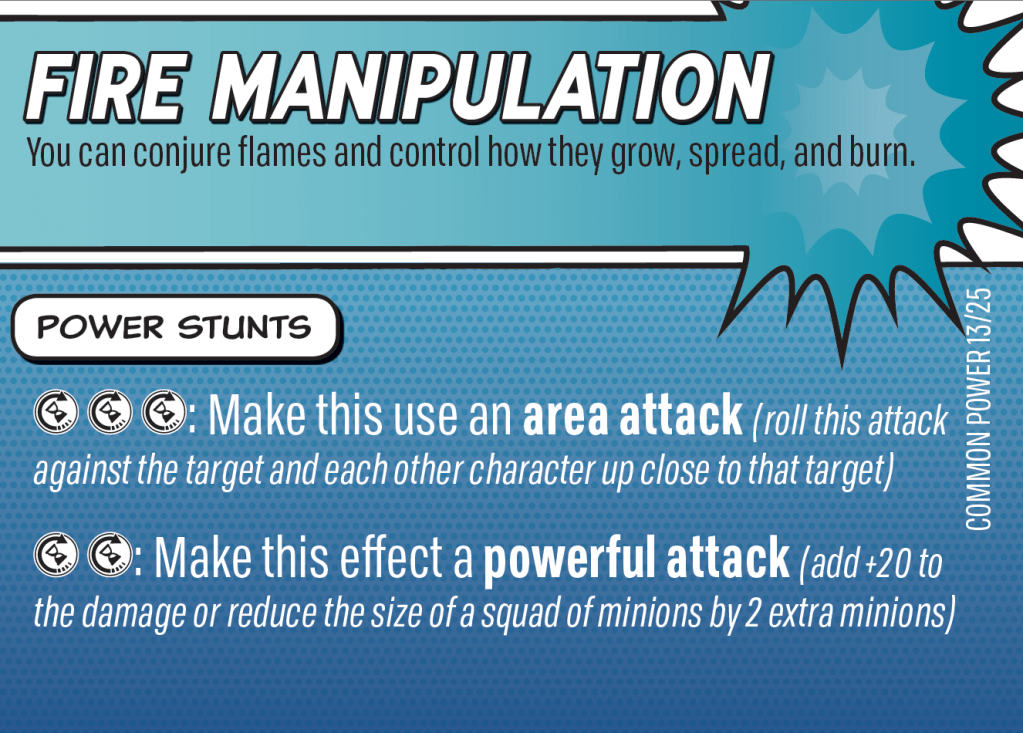

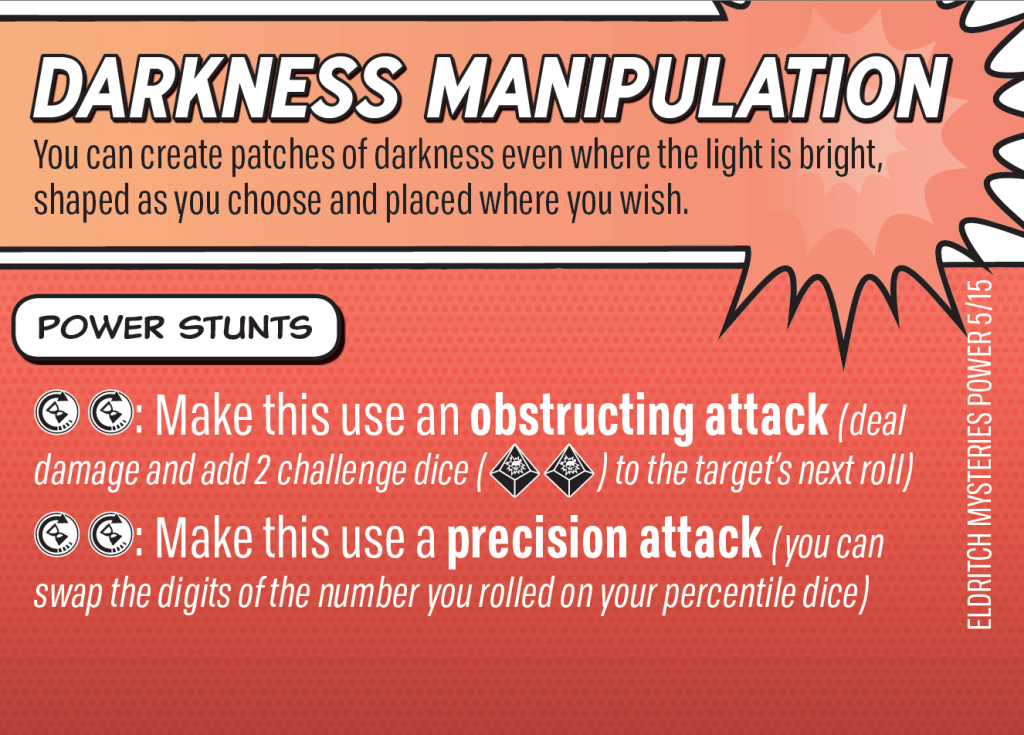

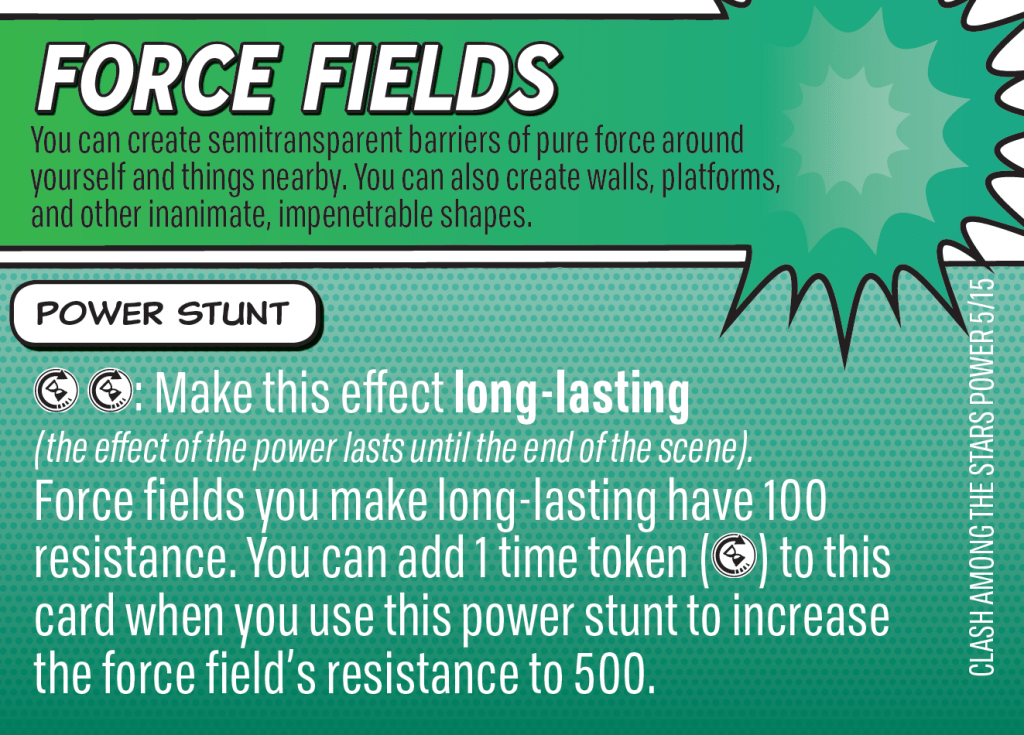

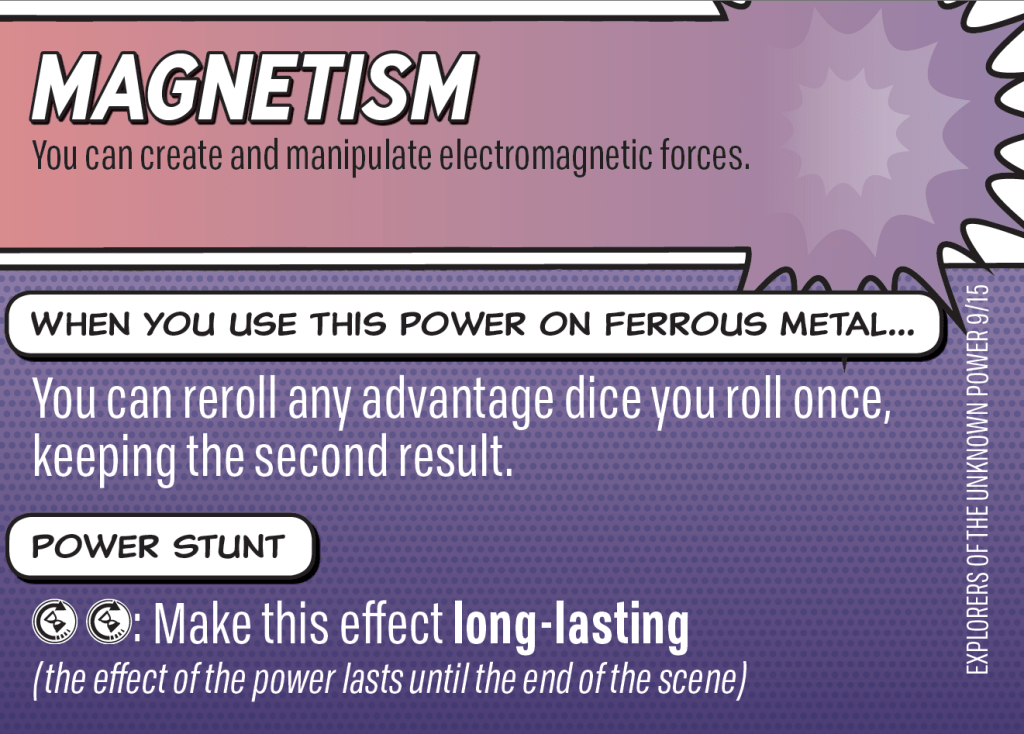

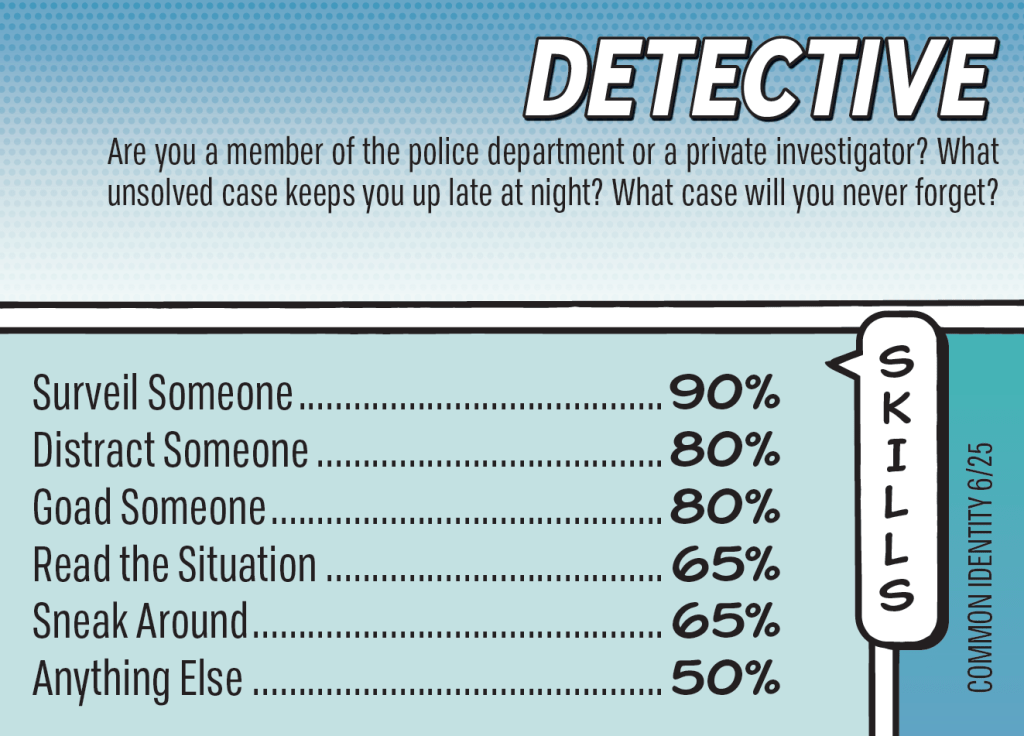

Then, you draw cards. Each series has a handful of Identity and Power cards, which are shuffled each into their own deck together with the respective generic Identity and Power cards. Each player gets three random Identity cards and five random power cards. That’s what they have to work with to build their hero (plus a choice of 5 basic powers like Super Strength).

Players can choose between 1 and 3 powers and 1 identity. Identities give the character skills, things they are good at. Each card also asks a few questions about how your identity comes into play, how it’s expressed. Everyone must choose one Super Power, which is slotted at the top of their character sheet’s Powers section. That’s the main thing they’re good at, the power with which they have the highest chance of success. They may also choose two more powers from their draw or the basic deck, but each extra power reduces the amount of Hero Points they have at the start of each conflict. Hero Points are covered in the Conflict section later on.

So, you pick an archetype, fill out a few questions, pick a randomly drawn identity, and 1-3 randomly drawn powers. Your character is done. You get to play your first sessions now.

Here are some examples of the different cards and archetypes.

Aspiration & Turmoil

After–and only after–your first complete issue, do you get to think about your origin story. Now that you played the character for at least one full session, used their identity in play, used their powers in a conflict, you should have a good idea of who this hero could be.

As part of this process, you define the character’s Aspiration and Turmoil. Aspirations are something the character wants to achieve. Whether that’s personal or world changing, it’s the most important thing to them. Turmoils, on the other hand, are something that’s holding them back. A secret, a relationship, a fear. Something that the hero needs to actively work on to make better or prevent from becoming a real problem.

Not only are these cool aspects of your character, they are super important for the game. Starting with the second issue that this character is part of, you get to create a personal interlude scene at the start of the sessions, addressing either the aspiration or the turmoil. You get to craft a situation in which your character is trying to achieve something, is confronted with a problem, or interacts with these aspects in some way. The GM will work with you to make the scene fun and challenging, and if you make it out okay, if you “succeed” either by rolling dice or roleplaying, you get to mark extra progression and get a special continuity token your team can use during the issue to turn the tides when things go bad.

I’ll talk about interlude scenes in a bit, because they make up half of the game’s pillars and are a great form of narrative play with lots of player agency.

A Game About Villains

The Roadkill is barely conscious, as the crime boss’s enforcer, The Avalanche, towers above him. “So, this is the vigilante the boss is worried about?” He scoffs. “Insect, nothing more.”

The pistons on his massive cybernetic arms rapidly fire up, sending small shockwaves through the room–a reminder of The Avalanche’s unrestrained violence, and a promise of what’s to come. If Roadkill can’t think of a clever play to get out from under this titan, he’ll be buried and crushed by the villain’s seismic power.

Unlike heroes, villain creation is a bit more straightforward. The GM gets to draw three cards from the current power deck and choose one of them. The rest, however, is less randomized and left to the GM to choose instead.

First of all, a given issue suggests which villain archetype to use. Of course, the GM is always free to bring in a previous villain if it serves the larger story better. The first page of the double-sided villain sheet has a questionnaire based on the chosen archetype (mad scientist; wrecking ball; crime boss), establishing the general motif of the villain. Who they are, what they do, what they look like, why they’re doing it, and so on.

The second page is their actual statistics used in a conflict scene. They have a power which they can use with 75% chance of success. They don’t, however, get access to any of the power’s stunts or special actions. Villain powers are more like skills for them. They get their special moves from their perks.

Every villain starts with two points for the GM to spend among their perks, which are themed around their archetype. Sometimes, they also start with some perks already unlocked. Some of the perks grant passive abilities that make life harder for the heroes, while others are active abilities that often have devastating effects but can only be used a limited amount.

My favorite part about perks is that, after every issue that included a villain, the GM gets to mark another point in their perks. Even if the villain wasn’t the main villain of the issue, but was thrown into the mix through a random complication, they now get to advance.

Each villain also has a weakness that players can exploit once they figure it out. The weakness is, as always, chosen from a short list by the GM.

Besides the standard villain archetype, the game also has a few variations:

Major Villains are more dangerous than regular villains, gaining three powers instead of one, and are much harder to defeat.

Minor Villains don’t usually get a statblock themselves. They usually appear within an issue, which details how they work–they’re basic attack, maybe a power, and how much resistance they get.

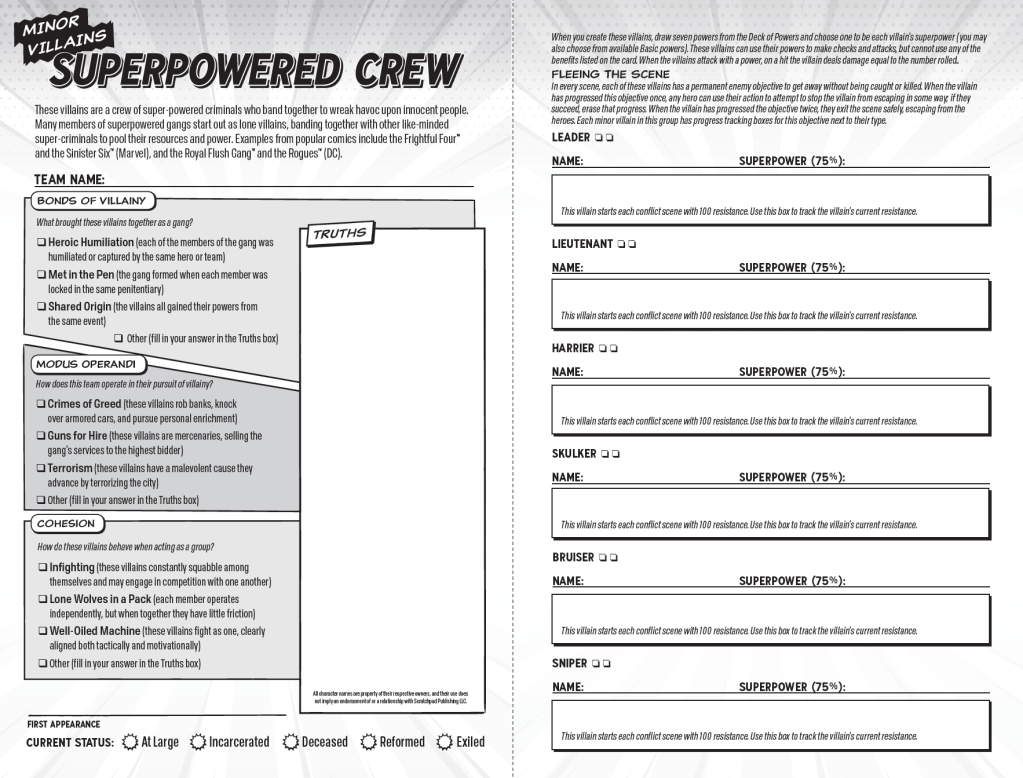

Minor Villain Teams, on the other hand, are made by the GM and feature a two-sided sheet, as well. As always, the first page lets the GM fill out the basic details on the team, why they work together, how much they like each other, and so on. The second page is just a list of all members, their role in the team, and a super power for each drawn from the deck. There are no other mechanics to a minor villain team.

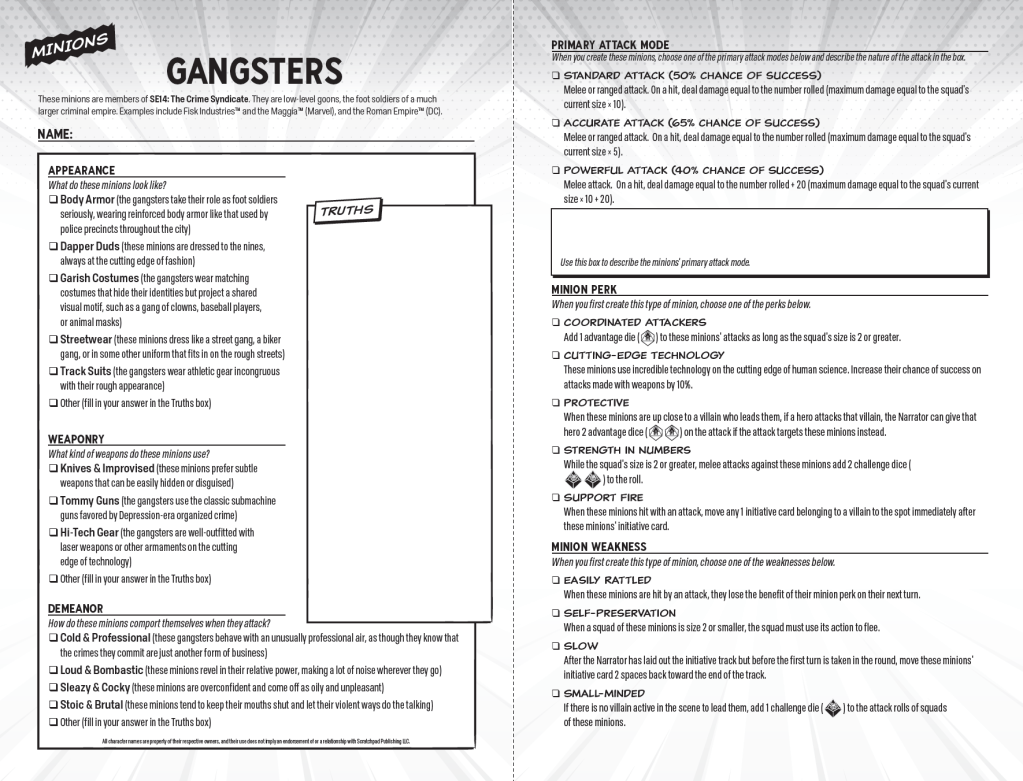

Finally, there are minions. Minions always come in groups with a size based on the amount of heroes in a scene, and they all act together as one. Most minions are detailed in a given issue, same as minor villains. There are some two-sided sheets for specific minions, who usually work for another villain and follow their general motif. The first page contains the details, the second is similar to the villain’s sheet. They only get an upgrade and a weakness, and never advance past that.

Here are some examples of the different villain sheets.

In general, villains are much easier to run than heroes. But their limited power set is always strong enough to make it extremely difficult for the heroes to win a fight against them. And they don’t always succeed, either. Villains getting away is a staple of the genre, after all.

My favorite part was always coming up with a cool name for my villains. A hyper intelligent foil to the rather violent streetlight knights? Checkmate. A cybernetically enhanced enforcer for the big crime boss that has seismic pistons built into his massive metal arms? Avalanche. A crazed lunatic who became a villain after being scarred by a hero in the very first issue, who seems to manipulate luck and chance instinctively? Miss Fortune. The minions of the crime boss who runs a mega corporation? Deniable Assets.

Listen, it’s all corny and cheesy. But that’s what makes it great. Comic books, as serious and dark as they can be, are meant to be fun and entertaining.

A Game About Setting

Atop Power Tower, the Professor stood and watched Edge City sprawl around him. He did everything he could to make this world a safer place, just to find it torn apart from beyond his own reality. From an alternate timeline, from the greatest threat he would ever face: himself.

He took another deep breath, just as a surge of power darkened the city for a heartbeat.

“We’re all set here, Prof. The artifact is stable now, though we won’t be able to hold the portal for long once we fully open it.” Benny spoke to him through their coms.

“Thanks, Benny. I’ll be right down.”

Others would have called him a monster, an abomination or pariah, but Professor Power saw in Benny a friend and colleague. One of the kindest, smarted people he had ever known.

He took one last look at this city, at his earth. What lay before him and his team might not grand them the luxury of a safe return. But he must face his evil self on the other side of reality, stop him from tearing the multiverse apart in his own, misguided attempt at saving his reality.

How far would he go to keep his world safe? Would he have used the Tempus Fidget artifact to rip a hole in spacetime to power his weapons and stop the alien threat in his own world?

He couldn’t answer this question, too afraid of the honesty of his answer. It broke his heart knowing that this other Self only did what he thought he had to.

If Spectaculars comes with a setting, it’s that of “Comic Books.” Not as in, it has the setting of any existing comic books. What it has is a setting book, filled with over 30 setting elements, each covering one classic comic book trope. The Artifact. The Megacorporation. The Government Agency. The Super Science Lab. The Nether Realm.

None of these elements are defined, however. Instead, they each come as a single page with a handful of short multiple choice prompts. All players at the table get to fill out, debate, interact with these prompts every time a new setting element comes up.

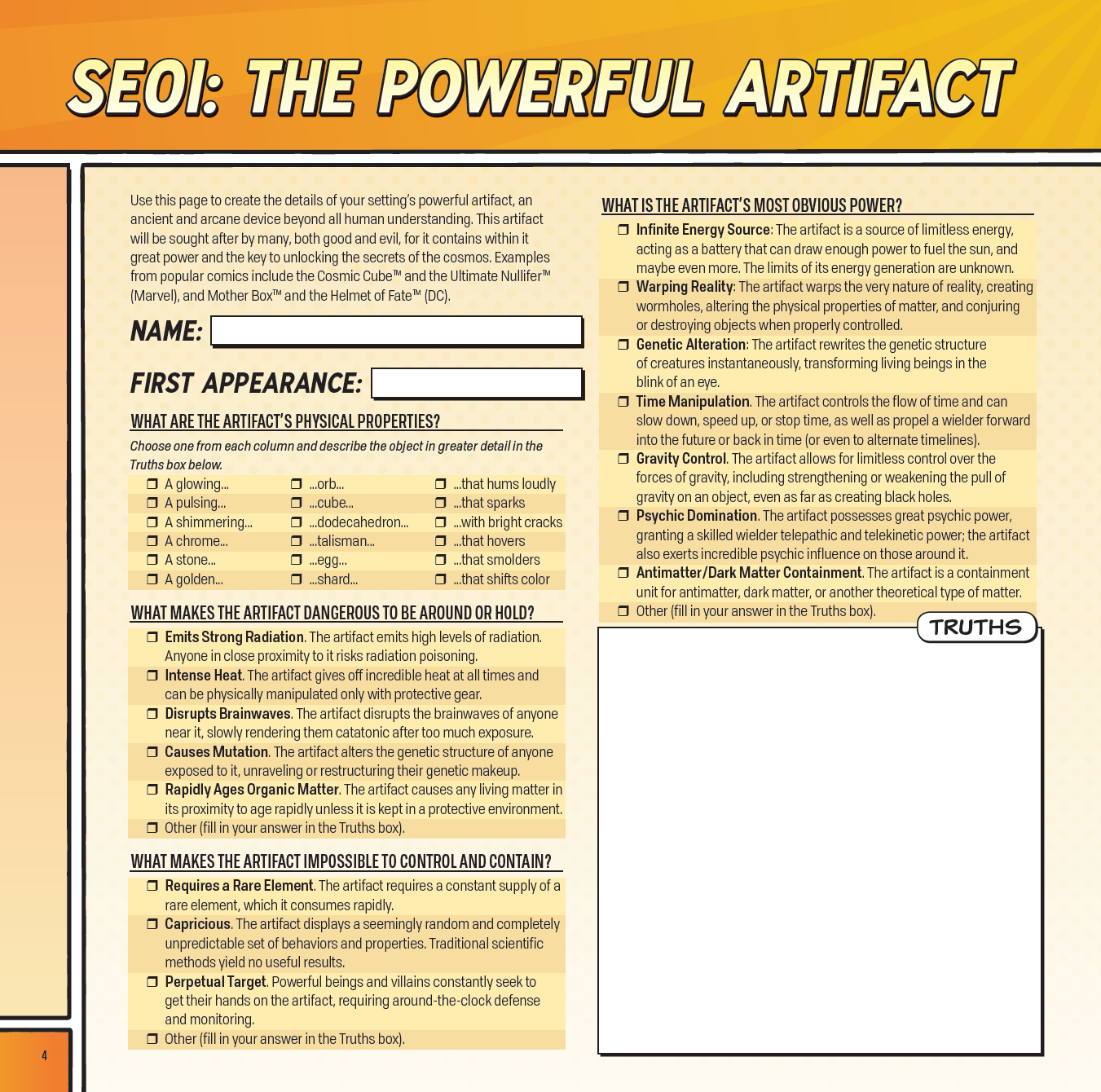

Here, take a look:

What makes this so special isn’t just that there are over 30 of these, each with their own tropes and flavors, but that you don’t fill them out until the first time they appear in a game. The moment the current issue (adventure) mentions, let’s say, the SE01: The Powerful Artifact, the GM and the current players open that page in the setting book and fill it out together. Notice the large Truths box, which is used to adjust or invent your own answers to each question, making that setting element truly your own. Though we found that we hardly needed that–the options provided were always great and inspiring as they came out of the box.

If you’re curious, here are the 30 setting elements and the 8 setting NPC archetypes. If you’re someone who enjoys comic books, I’m sure you already have some ideas as to what many of these titles refer to in your favorite comic book universe.

- The Powerful Artifact

- The Super Science Lab

- The Government Agency

- The Bad Neighborhood

- The Super Prison

- The Nether Realm

- The Star Empire

- The War-Torn Nation

- The Lost Civilization

- The Evil Dictatorship

- The Parallel Dimension

- The Forgotten City

- The Mystic Order

- The Crime Syndicate

- The Megacorporation

- The Alternate Reality

- The Hero Academy

- The Terrorist Group

- The Pariahs

- The Space Police Force

- The Starport

- The Distant World

- The Lawless City

- The Pariah Experiments

- The Secret Society

- The Superhuman Edict

- The Catastrophe

- The Dystopian Future

- The Golden Age

- The Sacred Site

- The Media Personality

- The Celebrity Bigot

- The Hateful Authority

- The Team Mentor

- The Mystic Sage

- The Agency Chief

- The Police Representative

- The Cosmic Liaison

The basic setting itself gets a two-page spread for the group to fill in the first time they get together to play the game. It established the general vibe, aesthetic, time period, and even how common heroes, villains, and their deaths are. That last point, how often heroes die in the line of duty, is actually mechanically relevant. The more lethal the game, the more likely the heroes are to fall to their villains. More on that in a bit, when we cover the rules of the game.

The same way you get to explore your character during the first session and start defining personal details at a later point, the setting is being explored one issue at a time. It gets even more interesting when you consider in which order you play the four given campaigns, or when you jump back and forth between them. Elements defined during the supernatural game will be created within a different context and vibe, and the element will now be defined through the lens of magic even when it comes up again during the super science run.

The longer you play, the more defined the setting becomes. The more real it feels. When we first started playing our game, we called the city “Edge City” because we couldn’t think of a name. It was a bit of a joke, because the basic setting truths were kind of edgy–dystopian, towering, massive class and wealth inequality, and all the other good cyberpunk-esque stuff. But now, after we played through all of the issues, laughed and screamed with all of the cool and silly and wild heroes and villains, Edge City is real. It’s the name of our main city in this comic book universe. In my mind, it stands alongside Gotham City. And all that came from exploring, debating, collaborating on each element as we went along, one session at a time.

I can’t overstate just how well designed this part of the game is. Rodney Thompson, the creator of the game, truly had his finger on the pulse of what makes a comic book universe come alive. He took all the tropes and cliches apart, and rebuilt them into the Spectacular’s setting book, giving each element a fine selection of possible options that reflect various comic book stories, universes, brands, and genres.

Shared Ownership

The setting is created and shared by the players at the table. This includes the characters, the heroes.

Once you create a hero and play through an issue with them, you establish their backstory, turmoil, and aspiration. After that, though, they go back into the box with everything else. They are not yours anymore. They belong to the setting now, and everyone could choose to play them at a later stage, taking ownership and credit for them for the next issue.

Think of it as different writers taking a stab at a hero during a comic run or TV show. This might be unorthodox, but it sure is a unique approach to character design and setting. After all, this entire comic universe is open and shared between everyone playing it. When you play a character, you make choices based on whatever notes were left on the sheet, and you will leave your own notes for the next player.

Our group wasn’t big enough to really leverage this design choice, though. We played mostly once a week and had the same 3-4 players, with me being the GM or Narrator for most of it. So everyone stuck to their own characters, because it was easier and more comfortable that way.

There was one notable exception I’d like to share.

Beith’ir, Dragonoid Galactic Bounty Hunter

One player created a Clash Among The Stars character that was a galactic bounty hunter named Beith’ir. He was a dragon-man with a laser rifle, all serious and cool. He played that character one time, because his “main” character for that series, Tempora, the Guardian of Time (who was part of the galactic police force, think Green Lantern Core just with cosmic weapons instead of rings), was kidnapped by alien evil doers. A short while later, they freed Time Knight, so the player went back to playing her instead of Beith’ir.

Later, I ran an Explorer of the Unknown issue where the team had to fight a massive kaiju from an alternate dimension. They couldn’t take it down. At best, they could distract it and lure it in a given direction for a short time. They made a plan to lure it to an old power facility where they used technobabble and the Powerful Artifact (The Tempus Fidget) to send the kaiju back to its native reality. The plan worked well, until one of the players rolled with 2 drawbacks, which I used to draw a card from the deck of complications. The card I got was one that introduced another hero into the scene who is there to help, but keeps getting in the way.

So I chose Beith’ir. The superhero space dragon-man with a laser gun came down to earth to help the helpless humans in dealing with this massive kaiju problem. The entire fight, Beith’ir managed to distract the kaiju away from where the team needed it to go, all the while screaming taunts at the top of his lungs like, “Come at me foul mega beast! I am Beith’ir, and I will take you down!” or “Fear not you tiny people, Beith’ir will deliver you from this monster!”

Somehow, in my mind, Beith’ir became a bit of a comic relief. And we all had a great time with this.

Later, another player had a character that was a hillbilly in space that was as powerful as superman, but had a lot of gambling debt to some space crime boss. The hero’s name was Clusterflux. After a few sessions, that player took the Team Up advance, which allowed him to choose another hero and bring them into a conflict scene once per issue. He had to change his turmoil to reflect this new relationship and decided that Beith’ir, who was a bounty hunter after all, was hunting Clusterflux across the galaxy to bring him in for all that debt. Every time he would use that advance to bring in Beith’ir, the bounty hunter set a trap for Clusterflux, like jumping out of the garbage or waiting at the top of an elevator, just to then get dragged into whatever conflict scene was happening. Being a hero, Beith’ir would help out for now, but he would get Clusterflux one of these days!

One player created this serious alien bounty hunter, the narrator later used him as a random complication, and another player then enhanced his own character’s story with him. The original player never touched the character again, as Beith’ir was now part of the setting and belonged to no one person anymore.

I wish we could have played with that concept of shared characters a bit more, and I think with a group of 5 or 6 regular players, it would come up more often.

AC 100 System

Benny liked walking in the park. Downtown Edge City made an effort to bring some natural aesthetic to its core, albeit enhanced with holo-sim technology. Regardless, the scientist enjoyed his time away from Power Tower and the constant fight against villains hellbend on destroying the city.

The people in the park take wide paths around him, though. Benny was a pariah, an abomination if the media is to be believed. A large monster in many eyes, despite all the good he has done for the people of Edge City.

A group of young punks and bullies approached him, tossing slurs and insults in his direction. Most days, Benny would just turn away and leave. Today, though, he decides to talk to them. Show them that he’s not a monster. That his kind are as normal as anyone.

It wouldn’t go well. The more he tried to get through to them, the more antagonistic they became. Eventually, Benny’s patience broke, his temper getting the better of him. They fled in fear, everyone in the park seeing nothing but a monster.

Spectaculars uses Rodney Thomson’s AC100 dice system he developed for previous titles such as Dusk City Outlaws.

It’s easy: You roll a d100 and try to roll equal to or under the rating of whatever power or skill you’re using. There are no modifiers added to the roll. If you lack a skill or power, you always have an assumed chance of 50%.

Often, you will add one to four advantage dice and/or one to four challenge dice. These dice don’t affect your chances or results, but add secondary effects or interesting moments to a roll regardless of outcome. They also cancel each other out one for one.

Advantage dice are d8 with half of the sides showing a boon symbol, and the other half being blank. Rolling with one or more boons means that the action itself has a boon. In narrative play, boons grant extra insights or opportunities, and can give the heroes extra hero tokens for their next conflict. During a conflict scene, boons can deal more damage, heal yourself, increase your efficiency when dealing with complications, or cause other effects that momentarily hinder your enemy.

Challenge dice are d10 with six sides showing a drawback symbol, and the rest being blank. Rolling with one or more drawbacks means the action itself comes with a drawback. During an interlude, drawbacks can make things harder for the heroes, leading them down unhelpful paths. During a fight, drawbacks can cause damage to the attacker, leaving them exposed, or even bring in brand new complications drawn from the special Deck of Complications (my favorite part).

The AC100 system is simple enough, but has enough depth through the use of Boons and Drawbacks to make rolls interesting beyond the binary pass/fail outcome.

Narrative: Interlude Scenes

After the funeral, The Rook stayed by her grave for a while longer. His entire family were military, they signed up to do their duty. To protect their country. To fight someone else’s war. But his sister died because she joined his fight to stop the city from being destroyed. She trusted his mission, as he trusted in Professor Power’s ability to change Edge City for the better.

The city is safe. She is dead. Nothing changed.

Specify one goal you want to accomplish during the scene (a specific piece of information, some asset or resource, the cooperation or aid of an individual, and so on), and describe the place you are going to get it. You then explain how you are going to get it and, if necessary, who you will interact with to get what you want.

That quote is at the heart of Spectacular’s narrative play, which makes up half of its core gameplay.

Interlude scenes are always created by the players and spotlight the hero whose player wants to create it. That means that all of narrative play is directly initiated and carried by player ambition and creativity. Of course, that doesn’t happen in a vacuum. The GM sets up the framework for the fiction, what the general goals are for the heroes, and sets the initial scene that kicks off the action. The GM will also work with the players to craft their desired interlude into an interesting scene, and presents challenges that might interfere with their heroes and their wants and needs. From there, roleplay springs naturally, creating a back and forth between players and the GM, referring back to the established setting elements (or defining a new one if it becomes relevant), and making a roll to see how it all resolves.

My favorite part about this approach to narrative play is the amount of power and agency given to the players. They don’t need to ask the GM for permission to do something in the fiction, as they create the scenes. It’s the GM’s job to introduce challenges and keep the context of the established narrative straight, of course. Maybe the heroes need to get information from the police about a string of gang violence, but in your setting, the police doesn’t like the heroes. Luckily, one of your heroes is a Detective during the day, so the player simply creates an interlude scene where they have a chat with the police representative (a setting element you get to define) to get access to the reports. The GM might make it challenging by telling the hero that this isn’t their case, or maybe someone is working hard to hide the evidence (the villain of the issue, maybe?). Some roleplay, maybe working the rapport between the police rep and the Detective, and maybe some sort of roll, and the heroes get their answer and can move to stop the gang violence.

A Ticking Clock

Most of the issues included in the box have a ticking clock in effect. Every time the players create an interlude scene, the GM gets to tick down that clock as the villain’s plans move forward in the background. In other words, while the players have a lot of power to create interlude scenes of their liking, every time they do so, the plot advances. And failing an interlude has the direct consequence of wasting time.

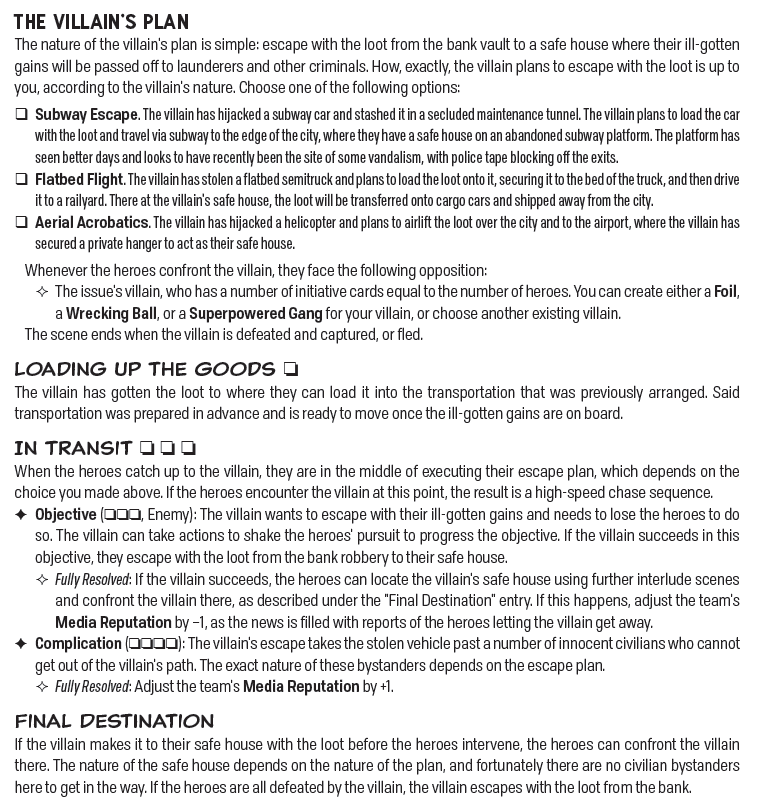

Usually, that clock is split up into narrative chunks–phases of the villain’s plot that, once completed, move the plot to the next chunk or phase. Let’s look at the very first issue recommended to be played: “Streetlight Knights #1: Breaking The Bank”

(Mild spoilers ahead for the issue, though the way the issues are set up, they could play out in so many different ways, it can’t really be spoiled too much ahead of time.)

In preparation to this, the GM first creates a villain (more on that later). Once that’s done, they get to choose one of three potential escape plans that the villain had. That choice is mostly just aesthetics, but it helps set the stage and maybe even give hints at the villain’s motifs and powers.

Actually, if you had to, you could run this issue without any prep. Just pick and fill out the suggested parts as they first come up. Though, it helps to know who the villain is ahead of time to guide the players’ investigation into the crime.

The issue starts with the heroes exploring the bank after the robbery and after the villain escaped already. They get to create interlude scenes to gather information on the villain, who they are, where they could have gone, and what they plan to do with the cash. Every time they create an interlude, however, the GM ticks the next available box of the villain’s plan. Once the last box of a given step is marked, that step is completed and the villain moves to the next step.

In the above example, the first interlude the characters create to start their investigation into the robbery will mark the first and only box of “Loading up the goods” and moves the villain’s plan to “In Transit.” If the heroes manage to catch up with the villain during this first interlude somehow, they might catch the villain just finishing to load their loot, ready to take off. They have two interludes to catch up with the villain while they are in transit, otherwise they catch up with the villain at their final destination.

Note that the villain won’t actually get away–the heroes will get to them eventually to have a final showdown with them. Wouldn’t be very cinematic otherwise. It also says that there are no innocent bystanders in the final phase, which is a good thing for the heroes, but actually a bad thing for the players. Saving people and preventing catastrophe during a conflict takes their attention away from the villain (who continues to attack them or advance their own objectives), but earns them Hero Tokens and potentially reputation with the people of the city. Hero Tokens are a vital resource in a fight and reputation can make interludes easier (or harder). Having no chance to earn those resources because it took you too long to catch up with the villain will make the fight harder.

This first issue is just a very simple example of how an issue plays out. Later scenarios get a lot more complicated or employ interesting mechanics. I won’t be spoiling any of those here though.

Aspiration & Turmoil Interludes

At the start of a session, before the issue starts, every character that has appeared in a previous issue (in other words, a character that has not just been created for this issue), gets the chance to create a special interlude scene associated with either their Aspiration or Turmoil.

These scenes offer a peek into the normal life of each hero, as they make efforts to reach their ambitions, or try to deal with their problems. During these scenes, they’re not caped crusaders fighting villains, but the people behind their masks trying to live their lives, before they’re drawn back into the conflicts that make them heroes.

This is one of the ways Spectaculars creates drama and conflict in the narrative, letting the characters breathe and develop as their personal journeys continue. It’s a vital part of what makes this game stand out to me.

Conflicts: Drama and Combat

Crackdown races his motorcycle at full speed over the edge of the bridge into the train yard, crashing it into the Misfit’s gangers currently engaged with his teammate, The Roadkill.

“About time you show up.” Roadkill’s voice crackles distorted through his helmet.

Two mooks go down in the crash, and Crackdown uses his own momentum to roll behind a train car. The gang members lose sight of him, even as they throw knives and clubs in his general direction. Roadkill finds himself surrounded by the Misfits, and even his hover-tank is being crawled on and beaten by the crazed gang members.

Out of nowhere, Crackdown appears again, striking from hiding and taking out several Misfits at a time, just to disappear again. Together, the two vigilantes take care of the remaining bad guys.

Crackdown throws the last Misfit before Roadkill’s feet. Roadkill grunts as his tank parks itself next to him. “I prefer a more direct fight, not this constant jumping around and hiding, you know.”

“Yeah, and your pretty armor is all scratched up now.” Crackdown gestures up and down his powered exoskeleton. “Good as new.”

Conflicts are an essential part of Spectaculars. Unlike narrative play, conflicts have more discrete rules, while also maintaining a strong focus on narrative flow and the drama and fiction of the fight.

Most, if not all, issues start with an open scene that is played as a conflict. Every story starts with something dramatic causing problems, forcing the heroes into action (often after their personal interludes) and setting them on the path of the scenario. Issues also often end with a final showdown with the villain(s).

When combat starts, the players and the GM build the Initiative Deck, which consists of one card for each hero based on their team role, one card for each minion group, and cards for critical complication and other special elements. Minor villains gain one or two cards, and main villains always gain as many cards as there are players. Yes, the villain of an issue acts multiple times. The villains also gain Resistance (health) equal to 100 times the number of cards they have at the start of the conflict. These cards are shuffled and laid out at the start every turn. Players and the GM might have means to manipulate the cards after they’re laid out, and some effects can affect cards even in the middle of a round.

Combat is abstract in all aspects. Distances are measured in abstract ranges (up close, near, far), and all actions, whether they use a power or a skill, are narrated to explain how they would benefit the attempted action. Players are encouraged to get creative with their power use–fire manipulation can set things on fire, control active flames, put fires out, or whatever else the player can envision to further the situation.

Attacks and other actions are resolved with the same 100AC system. Furthermore, if an attack hits, the number rolled is also the base damage dealt.

Tokens

Throughout the fight, the heroes juggle two different resources: Hero Tokens and Time Tokens.

Hero Tokens are spent by them to do cool things. Their team role, for example, lets them spend hero tokens to help out their team within their role’s capacity. A hero can spend hero tokens to add advantage dice to a roll of an ally in a teamwork maneuver. They are earned by doing heroic stuff, like saving people or stopping evil plots. Many archetypes have more ways to spend or gain hero tokens.

Time Tokens are placed on power cards to activate their special powers. You can always use your power in generic ways to address challenges or attacking enemies. But many of the special effects–stunts–are somewhat limited in their use. After using a stunt, place as many time tokens as it says on the card. At the start of each turn, you remove one time token from each card, meaning that some power can’t be used for a few rounds. Powers with time tokens on them also can’t be used for general actions, as the power itself needs to recharge in some manner fitting your hero’s motifs.

A special, third, token is called Continuity Token. These are earned with personal interludes at the start of an issue and can be spent for powerful effects that can turn the tides in a desperate moment. Spending these tokens can create flashbacks to a previous issue the hero was in from their back catalogue (not one you actually played), as a sort of flashback that highlights some advantage or insights they can leverage in the current situation. They can also create retcons to influence the current situation in interesting ways, like giving the villain a new weakness.

Complications & Objectives

Throughout a fight, the players might face one or more complications. These represent problems other than the villain(s) in a scene. Hostages, bystanders, burning buildings, ticking bombs, and so on. Addressing these complications is the hero-thing to do, and the players are rewarded with Hero Tokens when they take time to advance or finish them, even though the villains keep attacking them.

Objectives work similarly, but are mandatory to finish the conflict scene.

Complications and objectives have a number of boxes that need to be ticked before they are completed. Each ticked box grants the acting hero a Hero Token for their efforts.

Some complications can even be critical, which means they get their own initiative card. Whenever that card comes up, the last box of the complication is ticked, signaling some failure or growing threat. The heroes have limited time to complete that complication, adding drama and tension to the fight.

Some objectives can only be advanced by the villain(s) and only ever once per round, regardless of how many actions the bad guys get. Other objectives have two separate tracks for villains and heroes, and whichever side finished first, wins.

Complications and objectives are great mechanical ways to have stakes and tension, forcing the players to make tactical decisions and allowing them to earn hero tokens. Failing objectives also leads to interesting story beats as the villain succeeds at their evil plans. Not every issue ends in a success, which leads to drama, hardships, and consequences.

Spotlight

Iron Man upgrading to the Hulk Buster suit; Thor summoning a massive thunderstorm to bottleneck the alien portal; Spider-Man stopping the runaway train with all of his might and will.

Sometimes, a hero takes the spotlight and becomes larger than life. Whenever a hero rolls four boons on an action, they take the spotlight. Each archetype has different expressions for this–extra resistance, more actions/turns, more damage, free hero tokens, and so on. This can only ever happen once per conflict scene, and once a hero gets the spotlight, it lasts until the conflict is resolved.

It’s like rolling a critical hit in other games. It’s rare, it’s epic, and is often a turning point in the fight.

Whenever a player gets the spotlight, they get to describe how their hero transforms in some manner into their more powerful form. That alone is epic, and once they get to unleash their extra power, they truly feel like they are the MVP of the fight. It’s never not been great to watch unfold.

Since spotlight is based on rolling 4 boons on a single roll, players are eager to stack the deck in their favor. They use team up maneuvers to give allies more advantage dice to roll, prepare with special effects that grant extra advantage dice, and use their team roles and powers to allow for rerolls of advantage and challenge dice–all in hope to give each other the spotlight in a display of teamwork and excitement. It’s one of those things that makes this game shine, when it encourages players to work together to spotlight each other during a conflict, cheering when it happens regardless of who got it this time.

Hero Death

Every character in a conflict has Resistance–the amount of damage they can take before they’re taken out of the scene. Being reduced to 0 Resistance doesn’t mean death, it just means that the character is no longer part of the conflict for some reason.

However, if a villain reduces a hero to 0 Resistance and rolls a number of boons as part of that attack, the hero might actually die. Remember how I said earlier, during the Setting Book chapter, that your choice of “How often do heroes die?” has an actual effect on the mechanics? The more lethal your choice, the fewer boons a villain needs to kill a hero. A really lethal game only requires a single boon to kill a hero that was reduced to 0 resistance with the same attack. A more forgiving game requires three boons instead.

This is the only instance where a choice of a setting truth directly impacts the gameplay without the GM and the players adjudicating something on the fly as it would make sense in the fiction.

Heroes can be removed from the game in other ways, too, by taking an advance that forces them to “retire.” More on that in a bit.

The Other Stuff

There is plenty more going on with conflict scenes, like minion groups, using a villain’s weakness, area effects, lasting effects, and so on. I won’t be going into detail on those for sake of word count, but there is enough here to make combat feel varied and interesting. It’s no Pathfinder 2e or even D&D 5e with its mechanics or complexity, but it does enough to service the fiction of each villain, super power, and effect.

Even with all these systems in play–the tokens, the special effects, the cards, the complications–a conflict scene still feels like a narrative unfolding as the fight goes on. Every power, whether it uses a stunt or not, is used within the context and framing of the fiction as it happens. Yeah, you can use Fire Manipulation to free those hostages dangling over a vat of acid, if you can tell me how you would accomplish that.

Since distances and actions are abstract, conflicts can take place atop a moving train, or flying past skyscrapers as the villain and heroes duke it out. Clever use of the environment might convince the GM to grant extra advantage dice on actions, encouraging players to really lean into the fiction of the fight.

A Hero’s Journey: Advancement

Detective Malcolm Meles came home after a late night patrolling the streets of Grifter’s Ally. His nephew was supposed to be at sleep, but lately he has been staying up, waiting for his uncle to come home. Poor kid. After his entire family, including Malcolm’s sister, was murdered, the only person he had left was his uncle. And now Malcolm spends most of his nights out late, driving around in a modified military hover-tank, chasing down criminals whenever the system he pretends to care about fails.

Malcolm knew that he should be there for his nephew. That he should raise the boy in a safe and warm environment.

But the truth was, he didn’t feel warm or safe himself. Every day, he chased leads and arrested criminals, just to find them back on the streets a few days later. The whole system was corrupt. It’s all a massive failure. There was no justice without revenge.

Sometimes, even when he took his nephew in his arms after a late night out, he felt empty. Felt like the uncle was the mask worn by The Roadkill. A mask that would slip a little bit more each night.

Heroes earn advancement points after every issue they participated in, regardless of the outcome, and whenever they succeed on an aspiration or turmoil interlude scene. After collecting a few of these points, a hero gains a Reward!

Story rewards come in many different forms; from upgrading their abilities such as gaining extra hero tokens to start a fight with, making powers more reliable, gaining new skills, and so on. These are the less interesting upgrades, but they are always useful.

Revamp Rewards let you change parts of your hero, such as their actual powers, identities, and even archetypes. These are achieved in many different ways, such as technology, magic, alternate realities, taking up the mantle of a fallen hero, and so on. Each choice ties in directly with another setting element, so the entire group can be part of defining how these changes are happening for your hero.

Setting rewards establish new truths and elements for your setting that often affect your entire team. Gaining headquarters, vehicles, wards, government contracts, or creating a sentient being, a nemesis, and many, many more options.

Retirement Rewards let you end the career of your hero in many different ways. From losing their powers, to death, to passing the torch to a new hero, your hero’s story comes to end here. This reward can be chosen any time you get a reward, but must be chosen at the end of your advancement track. These endings don’t come into effect the moment you pick them, usually. Instead, you work with the GM and the group to make them meaningful during the next sessions.

Origin rewards are special rewards that are earned by playing the game, and are given to new characters. Many retirement rewards grant an origin reward for your next character, letting them start the game with a little boost.

Forth Wall-Breaking rewards are the most interesting type of reward to me. These rewards reinforce the idea that you’re creating and playing a comic book universe. Maybe there is an action figure line of your hero, which often comes with outlandish or strange features not usually found on the hero in the comics. Once per session, you can draw an additional power for one conflict scene and describe what toy that is based on. My favorite one is the Sponsorship deal. Your publisher made a deal to advertise a product in your comic. Come up with a cool product, and at the end of each session, one player MUST do an ad read, IN CHARACTER, for that product. That character also gains an additional advance for doing so. We got to a point where these ad reads happened at random points during the story, like when the team got suited up for a big fight, or traveled through space in their ship. Even demon infested hell dimension would find room for an ad for our gracious sponsor.

Repercussions

Each hero can have up to four repercussions they earn during the game. These are often given to them by fighting specific villains, or by failing objectives or entire issues. These repercussions are then later referenced, bringing in more drama and complications to the team.

Repercussions are a nice and simple way to tie different issues together to form a larger arc. Maybe you gained the “Vengeance of the Crime Boss” repercussion, because you were the most annoying to that crime boss when you brought him down. Later, when you face them again, they gain a bonus on attacking you specifically. Or you can use that consequence for the Nemesis setting rewards, establishing that this villain is more than just another criminal to you.

Maybe your media reputation was already low after you failed an objective, leading to you gaining a repercussion that turns the media against you. And a few issues later, a failure leads that repercussion to the government giving into the growing pressure from the hateful exposes on your team to enact a super-human edict, declaring you all criminals, or worse.

In some cases, these repercussions can lead to their own issues outside of the given campaign arc. Heroes being kidnapped or imprisoned can’t be used until they’re freed, so the team might want to look into that. This can open up the narrative in interesting ways not handled by the established series, allowing the group to create their own issues to expand their comic book universe.

Conclusion

Poltergeist did it. The ghost of the ancient wizard has reclaimed his power of the Nether Realm. The Reverie now lay before his mercy, as Poltergeist ascends the throne once held by the Warden. His former allies, the team of the Dreamcatcher, will come for him. Led by Agent LeShade and the mystic order of Maji, they will attempt to stop his influence over the waking world. The hero known as Poltergeist, the ancient wizard now becoming the new Warden of the Reverie, would not make the same mistakes as his predecessor. Hubris, arrogance, those were his downfall, too, a long time ago.

This time, he will be prepared. Old friendships be damned.

Over 50 sessions, an entire comic book universe later, Spectaculars has become one of my all time favorite games. So many heroes and villains, drama, heartbreak, victory, and stories were created using this game. Everything Spectaculars does lends itself to creating these elements, to telling these stories. Players are in charge during the interludes, empowered to put their characters in interesting and challenging situations to get what they want. The villains follow their own plans in the background, becoming more dangerous and powerful the longer the heroes take to find them.

The archetypes and powers, the advancements and consequences, the setting book, it all drives the game toward a fully realized comic book universe. Is it a perfect game? Of course not; all games have flaws or things that don’t quite work as well for everyone. But Spectacular’s strengths way outshine any shortcomings I came across, and all of them were minor enough to not even warrant a full breakdown here. This isn’t a critical review, after all.

You might think that 50 sessions isn’t all that much. After all, some D&D campaigns have been going for years! My group and I played through all four series books, played through all of their issues, and created a handful of our own as it made sense for the larger story. Each series guides you through a full story, from some simple early issues, to larger, multi-part conclusions to the bigger arc of the series. We could have played more. We wanted to, still do to this day. But we decided to go ahead and try out more games, turning our weekly Spectaculars game into a weekly try-out-different-games game. But we never felt like we didn’t get our money’s worth. We played through the entire box worth of adventures, explored so many different heroes and villains, genre and themes and motifs. I ran three out of the four campaigns. The fourth one, Eldritch Mysteries, was tackled by someone who has never run a game before. Spectaculars was (more or less) his first TTRPG ever, and the first one he ran no less. How cool is that? At the time of this writing, he’s running Triangle Agency for us, by the way. A game new to all of us, and he’s doing a fantastic job with it.

These stories, our stories, of Edge City stick with us to this day. In this post, every opening piece of fiction you read with each chapter are dramatized retellings of moments of our time with the game. The characters presented, the background setting hinted at, all happened when we played Spectaculars.

Rodney Thompson is a great game designer and has a strong handle on the tropes and genres that make comic books, comic books. He’s currently working on his next game: Neon City Outlaws, the cyberpunk reimagining of his previous game, Dusk City Outlaws. It had a successful Kickstarter and is currently in development. The thing I’m most excited about that game is that it will also have a setting book like Spectaculars, that lets you and your players create your own cyberpunk city and setting as you play. If it’s anything like the Spectaculars setting book, it’ll be the best cyberpunk game available. Guaranteed.

Spectaculars also had a successful Kickstarter campaign, and then it was released in early 2020. Maybe you are able to guess what that would mean for a box-set game that uses physical objects like cards and tokens. The world went quiet during the first years of the pandemic. Unfortunately, that meant that Spectaculars never got off the ground the way it deserved. It simply wasn’t possible for people to get together and play this game-in-a-box the way it was meant to be played. By the time in-person play resumed to some normal level, Spectaculars was already left behind. And that’s a real shame.

I managed to create my own Roll20 version of the game, painstakingly uploading each card and archetype sheet, creating macros for the dice system, using API scripts to shuffle cards and make it all work. I wasn’t the only one wanting to play the game despite the current hardships, so I opened the game up for the Roll20 community to join in. And a few people found it. Some of them are still around to this day, playing games every week with me. And we always–always–come back to Spectaculars. Reminiscing, wanting to return to it if not for the pile of games to try out and play.

Comic book stories are, at their core, no different than dramas, soaps, and action flicks. Just with costumes and superhuman powers. If that’s something you like, or if you want to play a game where every bit of its design and rules serves to build up and further that fantasy, Spectaculars by Scratchpad Publishing should be at the top of your to-play pile.